By Tela Wangeci

When the African Nations Championship finally rolled into East Africa under the CHAN Pamoja 2024 banner, Nairobi transformed into something more than just a co-host city. For Kenya, the tournament was not merely about football, it was a stage to prove that the country could rise above its own chaos and deliver both on the pitch and off it. Fans had waited more than a year for this moment. Originally scheduled for 2024, the tournament had to be pushed to August 2025 due to congested international calendars, logistical gaps in stadium readiness, and the complexities of coordinating three co-hosting nations: Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. The delay was frustrating for many, but in hindsight, it gave Kenya the breathing space to get Kasarani and other facilities to world-class standards, and to prepare its players mentally for the occasion.

The Harambee Stars, fielding a squad of CHAN-eligible home-based players, walked into the tournament carrying more baggage than most. Their federation, the Football Kenya Federation (FKF), was still battling reputational bruises. A FIFA suspension in 2022 had cast long shadows, while 2025 brought its own storms: Muhoroni Youth, a second-tier side, had been expelled from the National Super League for match manipulation and relegated to Division One. For ordinary fans, this fed a familiar narrative that Kenyan football was rotten at the core. And yet, amid the controversy, Kenya found itself the center of continental attention, asked to host one of CAF’s showcase tournaments and prove that the game here was still alive.

What gave the Harambee Stars a fighting chance in the face of so much instability was the arrival of a new figurehead: South African legend Benni McCarthy, appointed in March 2025. His resumé spoke for itself, Champions League winner with Porto, a former Bafana Bafana talisman, and a no-nonsense manager with a knack for instilling discipline. McCarthy wasted little time in reshaping the Harambee Stars. He picked form over reputation, demanded intensity in training, and drilled the squad on game management. His approach was pragmatic rather than romantic, but Kenya, so often a team that leaked goals or lost focus late, looked transformed almost overnight. They were compact without the ball, efficient going forward, and ruthless when opportunities came. More than tactics, McCarthy gave the team something they had lacked for years: belief.

That belief burst into life in the opening match at Kasarani against DR Congo. In front of a roaring crowd, Kenya stunned their visitors with a 1–0 victory, thanks to a sharp finish from Austin Odhiambo. The stadium erupted in unison, the goal marking not just the beginning of Kenya’s campaign, but a symbolic reclamation of pride. For once, Kenyan fans had a team to rally behind rather than complain about. The victory set the tone for the group stage, Kenya would not be bullied, not even by continental heavyweights.

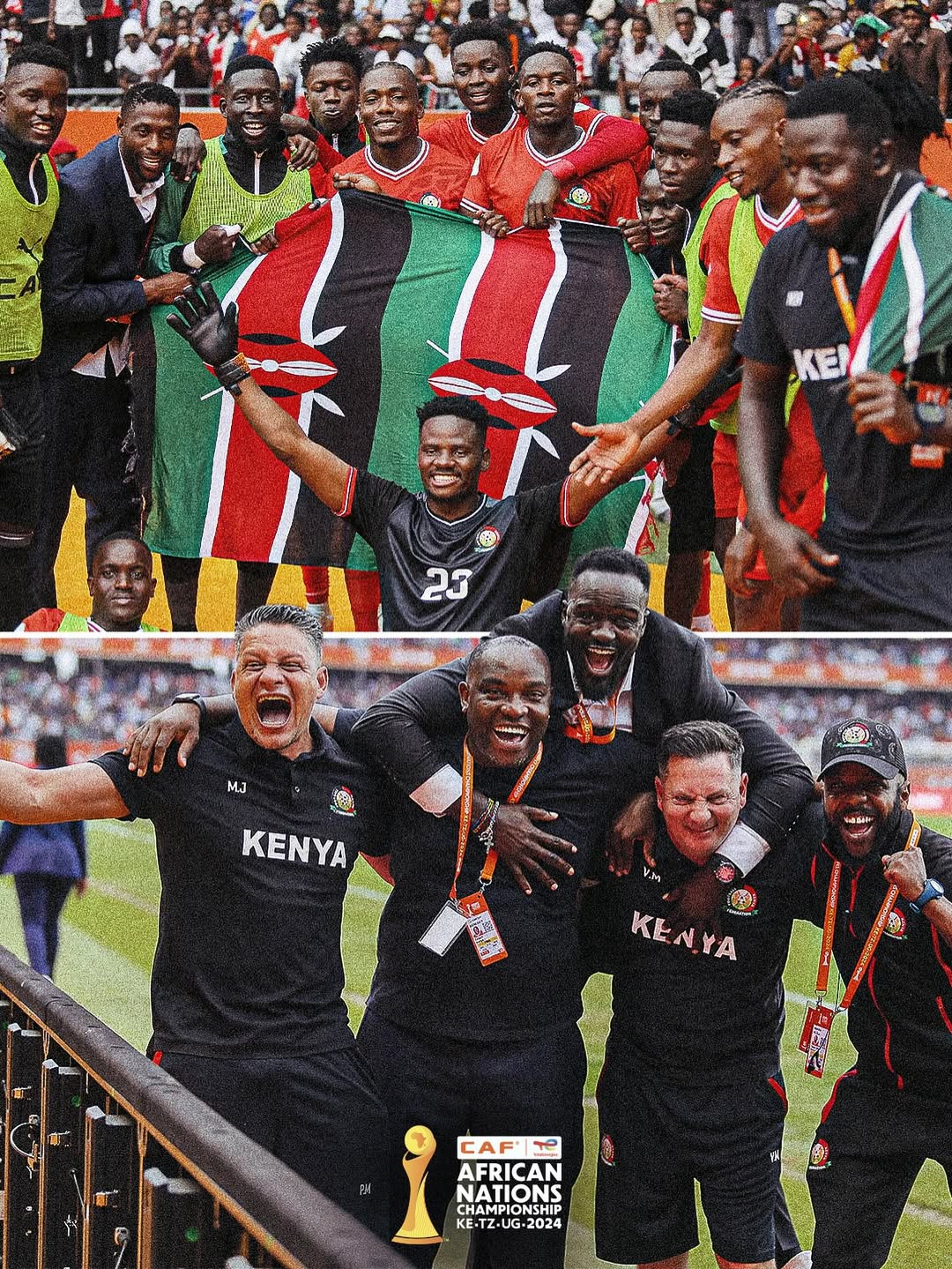

If DR Congo was the statement, Morocco was the miracle. Facing the defending champions, Kenya went a goal up through Ryan Wesley Ogam late in the first half. Just before the break, Chrispine Erambo received a red card after a VAR review, leaving the Stars to play the entire second half with ten men. It was here that McCarthy’s emphasis on discipline shone through. Kenya fought for every ball, blocked every shot, and trusted their goalkeeper, Bryne Omondi, to rise to the occasion. Omondi was inspired, making several critical saves that drew gasps from the crowd and groans from Moroccan strikers. When the final whistle blew on another 1–0 victory, Kasarani shook to its foundations. Ten men had held off Morocco, and in that moment, belief hardened into conviction: Kenya were not just participants, they were contenders.

The third group match against Zambia confirmed the momentum. Once again, Ogam was the difference-maker, scoring late to seal another 1–0 win. Kenya topped their group without conceding a single goal, each match a demonstration of resilience and opportunism. Omondi’s heroics in goal and Ogam’s clinical finishing defined the story, while Odhiambo’s opening strike set the narrative in motion. For a nation long starved of footballing glory, the Harambee Stars had become the darlings of CHAN, the team nobody wanted to face. Their journey ended in the quarter-finals against Madagascar, a goalless draw that went to penalties, where fortune deserted them. But even in defeat, Kenya bowed out unbeaten in regulation time, leaving the tournament with dignity intact and fans hungry for more.

What set this CHAN apart, however, was not just the football but the way it united the country. For weeks, politics, tribal divisions, and the usual national anxieties seemed to pause whenever the Harambee Stars played. Across Nairobi’s estates, Mombasa’s coastal streets, Kisumu’s bars, and village markets in Eldoret and Nyeri, Kenyans huddled around screens big and small, sharing joy and heartbreak as one. Strangers hugged in celebration, flags waved from matatus, and conversations that normally broke along tribal or political lines found common ground in football. For a nation often fragmented, the Harambee Stars offered a rare moment of harmony. More than just matches, these nights of football rejuvenated the Kenyan sporting spirit. They reminded people why football has always been called the “people’s game”: it belongs to everyone.

Off the pitch, though, the cracks in Kenyan football’s foundations continued to show. Ticketing chaos marred the tournament. Before the quarter-final, the official online portal crashed, locking out thousands of eager supporters. Security lapses at Kasarani had already led to CAF fines earlier in the competition. Each mishap underlined the broader question: could Kenya host world-class football smoothly? The Federation’s defensive statements did little to inspire confidence. These weren’t just isolated incidents, they were symptoms of an institution still struggling to match ambition with execution. Supporters who had shown up in their thousands deserved better.

View this post on Instagram

And yet, another narrative was unfolding parallel to the action: that of presidential incentives. President William Ruto took an unusually hands-on approach during CHAN, promising substantial financial rewards for victories. Every player was promised KSh 1 million per win, a figure later raised to KSh 2.5 million for the Zambia match. The President even pledged additional benefits, including affordable housing units, and floated a mega bonus pool if Kenya went all the way. After the Morocco win, he delivered on his promise, paying players and technical staff the KSh 1 million. For a national team long accustomed to government promises that evaporated, this follow-through was a seismic shift. Suddenly, the Harambee Stars were not only playing for pride, they were playing for tangible, immediate reward.

Did the money matter? Absolutely. While no bonus can conjure the grit required to survive 45 minutes against Morocco with ten men, incentives sharpen focus. They create a sense that the country is invested, that sacrifice will be matched with appreciation. Players walked onto the pitch knowing that victory would change not just their careers but their families’ lives. Yet the symbolism cut deeper. The President’s promises contrasted sharply with the federation’s missteps, creating a paradox: at the very moment the Harambee Stars were most unified, the structures meant to support them looked the most fragile.

This contradiction sits at the heart of Kenyan football today. On one hand, the Harambee Stars have proven that with proper coaching, motivation, and a supportive public, they can stand toe-to-toe with Africa’s best. On the other hand, the FKF continues to stumble over issues of governance, transparency, and professionalism. You can’t buy your way out of crumbling ticketing systems, preventable security fines, or the reputational damage of match-fixing scandals. Presidential carrots can fire up a squad, but unless the federation fixes the basics, calendar management, clean governance, fan trust the ceiling will remain lower than the talent deserves.

Still, CHAN 2024 offered something Kenya has not had in years: a blueprint. Compact defence, opportunistic attacking, and inspired goalkeeping proved enough to topple giants. Fans turned out in their thousands despite the hurdles, their energy lifting the team in crucial moments. The Harambee Stars’ run didn’t just deliver results, it delivered unity. For once, Kenyans could look past their divisions and see themselves reflected in one team, one jersey, one heartbeat. It was a rejuvenation of football culture in the country, a reminder of why the game matters so deeply here.

The Harambee Stars may not have lifted the CHAN trophy, but they lifted something arguably more important: the faith of a nation. Now, the challenge is whether those who run the game can match the courage of those who play it.